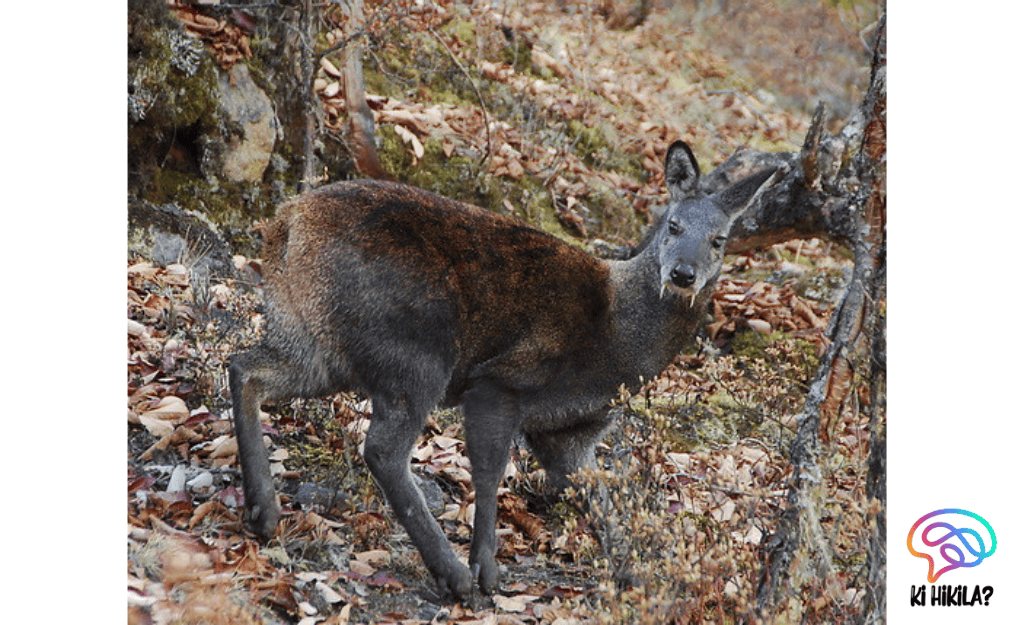

Alpine Musk Deer Conservation in India has reached a critical juncture, as recent findings reveal major setbacks caused by species misidentification and ineffective management. The endangered Moschus chrysogaster, commonly known as the Alpine musk deer, continues to suffer from population decline due to confusion with the Himalayan musk deer (Moschus leucogaster) in breeding centres.

A December 2024 report by the Central Zoo Authority (CZA) has highlighted systemic errors in India’s captive breeding programmes, exposing a worrying lack of precision in wildlife conservation efforts for this elusive Himalayan species.

Species Misidentification Undermining Conservation

The Alpine musk deer and Himalayan musk deer have overlapping ranges across the central and eastern Himalayas, leading to significant identification challenges. These two species exhibit similar physical traits and behaviors, complicating their distinction without genetic verification.

Zoos in India, including the Musk Deer Breeding Centre near Chopta in Uttarakhand and the Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park in Darjeeling, are believed to have housed Alpine musk deer. However, the CZA report reveals that these centres inadvertently ran breeding programmes for Himalayan musk deer instead. As a result, a dedicated captive population of Alpine musk deer has yet to be properly established, threatening long-term species survival.

Population Status: Decline Without Data

The situation is further aggravated by the absence of recent population assessments. In the 1980s, around 1,000 Alpine musk deer were estimated to exist in the wild. Today, no reliable data is available, making it difficult to track conservation progress or set goals.

In 2014, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) designated the Alpine musk deer as “Critically Endangered.” This classification reflects the species’ rapidly decreasing population and increased poaching threats, mainly for its musk pod—a highly valuable substance used in traditional medicine and perfumery.

Central Zoo Authority and Its Expanding Role

The Central Zoo Authority (CZA), established in 1992 under the Wild Life (Protection) Act, oversees and regulates captive breeding initiatives for endangered species in India. With the 2022 amendment to the Act, conservation breeding centres were formally recognised as zoos, broadening the CZA’s regulatory scope.

Despite this mandate, the CZA’s management and monitoring efforts for Alpine musk deer conservation have come under scrutiny. The confusion between species suggests a gap in scientific oversight, accurate animal tagging, and genetic testing protocols within breeding facilities.

Financial Allocations and Lack of Transparency

From 2006 to 2021, nearly ₹29 crore was allocated by the Indian government to various zoos for conservation breeding programmes. However, there is no publicly available breakdown of how much was specifically spent on Alpine Musk Deer Conservation.

The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) has acknowledged that the responsibility for financial disbursement and programme execution lies primarily with state authorities. This decentralized approach, while encouraging local ownership, has resulted in fragmented record-keeping and low accountability. Without precise reporting, it becomes difficult to assess the actual impact of these multi-crore investments.

Future Directions and Recommendations

In its latest report, the CZA recommended that no new species be added to captive breeding programmes until management and identification practices for existing species improve. A major proposal is for India to establish its own national Red List of threatened species, given that the IUCN’s global classifications may not accurately reflect species’ status within the country.

Improved scientific protocols, including genetic testing and microchipping, are essential to ensure accurate species identification in zoos and breeding centres. Additionally, transparent reporting mechanisms and third-party audits could strengthen public confidence and improve programme outcomes.

Conclusion

Alpine Musk Deer Conservation in India stands at a pivotal crossroads. The combination of species misidentification, poor monitoring, and lack of transparent fund utilization has severely weakened efforts to save one of the Himalayas’ most threatened mammals. Unless immediate corrective measures are adopted—both scientifically and administratively—India risks losing a vital component of its high-altitude biodiversity.

As conservationists, policymakers, and researchers reflect on these findings, the way forward lies in a coordinated, science-driven approach that prioritizes accuracy, accountability, and ecological urgency.