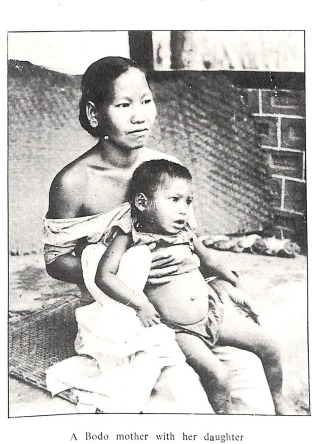

The Bodo-Kachari tribe, one of Assam’s largest and most prominent indigenous communities, belongs to the Indo-Mongoloid family of the Assam-Burmese linguistic group. Despite being unified under the broader Bodo identity, they are known by various names across regions—Meches in Bengal and Nepal, Dimasa in North Cachar, Barmans in Cachar, and Sonowal or Thengal Kacharis in Upper Assam. In Western Assam, they are commonly referred to as Boros or Boro-Kacharis.

By the 1971 census, the tribe numbered over 6 lakh in Assam alone, comprising nearly 45% of the state’s tribal population. Physically, they exhibit strong Mongoloid features—prominent cheekbones, slit eyes, sparse facial hair, and short, stocky builds. However, intermarriage and cultural assimilation have introduced noticeable diversity in their appearance.

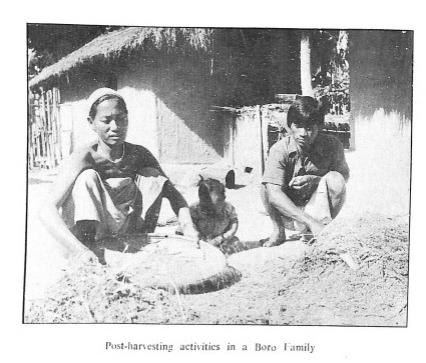

Livelihood and Agrarian Life

Agriculture is central to the Bodo-Kachari way of life. They cultivate both Ahu (autumn) and Sali (winter) paddy, often employing traditional irrigation methods that demonstrate sophisticated knowledge of canal systems and embankments. Rev. S. Endle, in his writings, lauded their cooperative spirit and ingenuity in building irrigation networks to counter erratic rainfall.

Their practice of setting up community granaries and village-based mutual aid reflects a deeply rooted cooperative ethos. Youth clubs and local funds, raised through collective labor, sustain social development and community welfare.

Social Structure and Customary Laws of the Bodo-Kachari Tribe of Assam

The Bodo-Kachari society follows a patrilineal lineage system. Inheritance rights are shared among male members, with special provisions for the eldest male and unmarried sons. A council of elders, known as Hadengoura and Hachung-Goura, enforces customary laws within village clusters. These are unwritten manuscripts, known as Pandulipis, and vary from region to region.

Village institutions like the Gaonbura (headman), Halmazi (messenger), and Douri/Deuri (religious functionary) form the backbone of governance and ritual life. These roles are merit-based and open to any capable individual, making Bodo society notably democratic in structure.

The tribe is divided into around 23 exogamous clans (called Ari) such as Basumatary, Narzari, Swargiari, and others—each originally associated with traditional occupations.

Religious Beliefs and Rituals

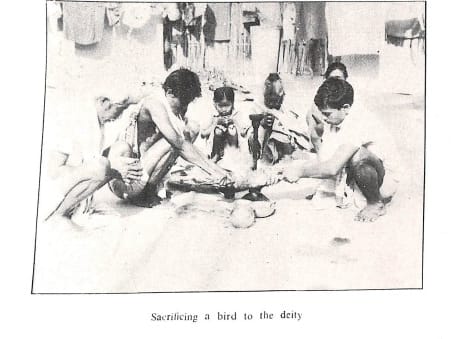

The Bodo-Kachari spiritual world revolves around Bathou Barai, equated with Lord Shiva. The Sizu plant (Euphorbia Splendens) symbolizes Bathou and is planted in household courtyards alongside basil and jatropha. Other deities like Mainao (goddess of wealth), Sali Mainao, Asu Mainao, and a pantheon of both benevolent and malevolent spirits are worshipped through offerings, animal sacrifices, and rice beer.

A significant religious divergence is observed between the traditionalists and Brahmas—followers of the reformed Vedic-based Brahma Dharma, introduced by Guru Kalicharan Brahma. The Brahmas perform Hom Yojna instead of animal sacrifices and rice beer offerings, though culturally, they remain intertwined with traditional Bodos.

Festivals and Celebrations of The Bodo-Kachari Tribe of Assam

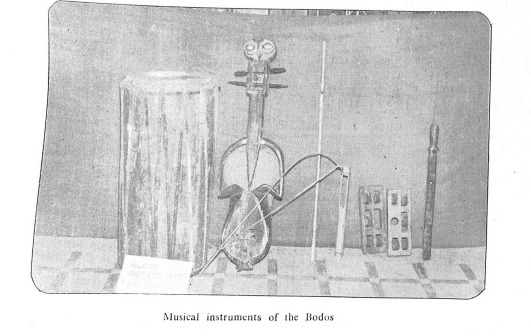

The most prominent festival of the Bodo-Kachari tribe is Baishagu, celebrated in mid-April, marking the New Year. It involves cow worship, offering reverence to elders, rituals for Bathou, and seven days of music, dance, and feasting. Traditional instruments like the Kham, Siphung (flute), and Gogona accompany the dances.

Other notable festivals include:

- Domashi and Katrigacha (Kangali Bihu) – harvest-based celebrations.

- Kherai – a major religious festival involving 20 ritual dances and possession ceremonies by the Doudini (female oracle).

- Fushihaba (Putuli Haba) – a symbolic folk wedding of Shiva and Parvati.

The Bagrumba dance, performed by women after the planting season, celebrates femininity and artistry, with participants donning handwoven traditional dresses.

Marriage Customs and Ceremonies

Traditionally, the Bodo-Kacharis practice clan exogamy, though this norm has softened over time. Several forms of marriage exist:

- Negotiation marriage (Hathachuni) – the most common, culturally approved form.

- Marriage by servitude (Chawdang Jagarnay) – now fading, where the groom works for the bride’s family.

- Widow remarriage (Dhoka) – permissible with clan induction of the groom.

- Voluntary union (Khar-Chanai) – a live-in relationship sanctified later.

In the Hathachuni ritual, the bride cooks a symbolic meal and distributes it to her husband and guests, marking the marital bond. Distinct differences exist between Brahma and traditionalist marriage rites, reflecting dual streams within Bodo religious life.

Birth and Death Rituals

Bodo-Kacharis do not follow orthodox Hindu birth rites. A cock or hen is sacrificed, and midwives are honored for their service. In death, cremation is preferred today, though burial and even exposure in open fields (for scavenging) have historical precedence—believed to cleanse the soul.

Mourning includes sanctified water (santijal) and bitter leaves (sokota) to sever ties with the dead. The Dasa and final Shradha rituals are performed on the 10th and 13th day, or later depending on the family’s capacity.

Language and Literature

The Bodo language belongs to the Tibeto-Burman family. Four major dialects exist across Assam. Though it lacked a script historically, Devanagari has been adopted since 1975.

From oral traditions, Bodo literature has evolved significantly, especially post the Brahma reform movement. The Bodo Sahitya Sabha (formed in 1952) has nurtured genres like poetry, fiction, and drama. Authors like Promod Brahma, Ishan Mushahari, and Sitanath Brahma Choudhury have enriched Bodo literary heritage.

Transformation and Modern Trends

The 19th-century Brahma Movement sparked a wave of social reform—promoting education, curbing dowry and alcoholism, and advancing Vedic values. Leaders like Rupnath Brahma and Sitanath Brahma Choudhury emerged from this renaissance, shaping Bodo politics and education.

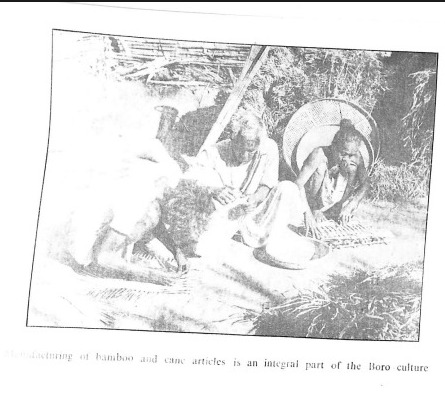

Agricultural diversification has followed, with many Bodo farmers now cultivating cash crops like jute, coriander, sugarcane, and arecanut. Sericulture and handloom weaving, especially of Endi silk, are major household industries, showcasing women’s craftsmanship in garments like Dokhona.

With education, many youths have entered government, paramedical, and technical professions. Development programs and microfinance have empowered them toward self-employment—especially in Kokrajhar and Kamrup districts.

Conclusion: Preserving Heritage in Changing Times

From animistic traditions and clan-based societies to modern education and politics, the Bodo-Kachari tribe has navigated a long journey of transformation. Yet, their identity remains deeply rooted in a rich cultural past—manifested through festivals, folklore, traditional attire, and community institutions.

The story of the Bodo-Kacharis is not just one of survival but of resilience, adaptation, and cultural pride—serving as a vital chapter in the ethnographic narrative of Assam.