The Barmans Tribe of Assam represents one of the significant plains tribes of the Barak Valley. They are an integral part of the greater Dimasa Kachari society, originally from the North Cachar Hills. Essentially, the Dimasas who migrated to the plains of Cachar came to be known as the Barmans. Over centuries, they have maintained their ethnic identity while adopting aspects of Hinduism and integrating with the cultures of neighboring communities.

Historical Background of The Barmans Tribe of Assam

The history of the Barmans is deeply intertwined with the legacy of the Dimasa Kacharis. In 1536 A.D., the Ahoms occupied Dimapur, forcing the Kachari king and his royal family to flee. The displaced Kacharis established their capital at Maibang in the North Cachar Hills. However, the ongoing conflicts with the Ahoms compelled Kachari king Tamradhaj to move to Khaspur in the plains of Cachar in 1706 A.D., which later became the permanent capital during the reign of Kartik or Kirti Chandra Narayan in 1750.

The term “Barman” itself is significant. According to scholars like Upendra Chandra Guha, the Dimasas who considered themselves descendants of Bhima, the second Pandava of the Mahabharata, and adopted Hindu religious practices, were called Barmans. This distinction from the traditional Dimasa religion, which traced lineage to Hidimba, established the unique identity of the Barmans in Cachar. Over time, they adopted Hindu customs, including wearing the sacred thread, and the influence of Brahmins cemented the use of the Barman title across the plains Dimasa population.

Significance of the Name “Barman”

The term “Barman” distinguishes the plains Dimasas from those still residing in the hills. Scholars suggest that the Dimasas who claim descent from Bhima, the second Pandava of Mahabharata, and follow Hindu religious practices are referred to as Barmans. The adoption of Hindu customs, such as wearing sacred threads, was influenced by Brahminical priests and interactions with neighboring Hindu communities.

By contrast, Dimasas who continued traditional practices in the hills are known as Dimasa. The Barman title gradually extended from the royal family to common people by 1830, signifying their full acceptance of Hindu rituals and identification with the Kshatriya caste.

Racial and Linguistic Affinity of The Barmans Tribe of Assam

The Barmans of Cachar belong to the Tibeto-Burman group of people, originally migrating from areas along the Yangtze River and the Howaog-Ho in western China. They share ancestry with the Bodo-Kacharis of the Brahmaputra Valley and the Dimasas of the North Cachar Hills and Karbi Anglong. Over centuries, geographical isolation and interaction with neighboring communities have led to distinct linguistic and cultural characteristics, though they remain connected by their shared heritage.

Demography

As per the 1971 Census, the Barmans population in Cachar was 13,210, slightly higher in literacy rate (30.45%) than the state average. Males showed 39.97% literacy, while females were at 22.56%. Though dispersed across villages in Silchar and Hailakandi subdivisions, the Barmans maintain a cohesive cultural identity despite external influences.

Social Structure of The Barmans Tribe of Assam

Family System

The Barmans follow a patriarchal and joint family system. Multiple generations, including sons, daughters, and unmarried brothers, live together under one roof—a structure influenced by neighboring Bengali culture.

Clans

They have 40 male clans (Semphong) and 42 female clans (Julu), which are exogamous. The clan of a newborn is determined by gender: boys inherit their father’s clan and girls their mother’s.

Marriage Customs

Marriage by negotiation is common, while traditional Dimasa practices have largely been replaced by Hindu rituals conducted by Brahmin priests. Monogamy is the norm, and bride price, called “Kalti,” is now rarely insisted upon. Child marriage is uncommon, and divorce is laborious and rare. Widow remarriage is not practiced among the Barmans.

Birth and Death Rituals

The birth of a child is celebrated, with purification ceremonies and offerings to midwives. Deaths are mostly cremations, except for infants. Rituals are performed to ensure the departed soul’s safe rebirth. Special fear surrounds deaths due to childbirth or tiger attacks.

Law of Inheritance

Inheritance is guided by dual clan structures. Paternal property passes to sons, maternal property to daughters, while shared household items are divided equally. Childless relatives often inherit debts and property obligations, sometimes causing financial strain.

Village and Leadership of The Barmans Tribe of Assam

Barman villages in Cachar are carefully organized and reflect the influence of neighboring Bengali settlements, with large, spacious homes oriented mostly towards the east or south to maximize sunlight and ventilation. Each household typically maintains a small kitchen garden, fruit trees such as mango, guava, jackfruit, and banana, and bamboo clumps, contributing to both sustenance and aesthetic appeal. Sanitation standards in Barman villages are notably high, with separate structures for kitchens, granaries, livestock, and sometimes even guest accommodations. Ponds for drinking water are common among well-to-do families, while timber posts and mud-plastered walls, often topped with thatched or C.I. sheet roofs, form the basic architecture. Traditionally, village leadership was held by the Kunang (headman) and assisted by the Dilo, who played crucial roles in decision-making, dispute resolution, and maintaining social harmony. Over time, these traditional systems have largely been replaced or supplemented by modern administrative structures, including government-appointed Gaonburahs, Panchayat members, members of the Integrated Tribal Development Project, and educated village elders who often mediate conflicts. Despite modern influences, the villages continue to retain strong communal bonds, and inter-village disputes are usually addressed first through council deliberations, reflecting a preference for local resolution and community cohesion before legal intervention is sought.

Education and Bachelors’ Dormitories of The Barmans Tribe of Assam

Unlike their Dimasa counterparts in the North Cachar Hills, the Barmans of Cachar do not maintain bachelors’ dormitories, locally known as Nodrang. In the hills, these institutions served as centers for training young men in warfare, discipline, and community responsibilities, but in the plains, the relative security of village life and the influence of modern schooling systems gradually rendered them unnecessary. Instead, education became the key to social advancement. The Barmans show an impressive inclination towards literacy, which has historically remained above the state average. Parents strongly encourage both boys and girls to attend school, and many pursue higher education, securing jobs in government service, teaching, and administration. This focus on education has helped the community adapt to changing socio-economic conditions while preserving cultural pride. The absence of Nodrang thus symbolizes a transition from traditional systems to a modern outlook centered on formal education and community progress.

Religious Life of The Barmans Tribe of Assam

The religious life of the Barmans reflects a fascinating blend of Hinduism and traditional tribal beliefs. Over the centuries, under the influence of the Kachari kings and Brahmin priests, the community gradually embraced Hinduism, particularly the Sakta sect, which emphasizes the worship of powerful deities like Durga and Kali. Despite this transition, many ancestral customs and rituals were preserved, creating a unique religious identity that blends orthodoxy with indigenous traditions. Lord Siva, locally revered as Sibsrai, continues to occupy a central place in their belief system, symbolizing both protection and fertility. Rituals related to birth, death, and agricultural cycles often invoke his blessings, showing how spiritual life is intertwined with everyday survival. Interestingly, unlike several other tribal groups of Assam, the Barmans have remained untouched by Christian missionary influence, maintaining continuity in their religious heritage. Their temples, seasonal festivals, and household shrines thus stand as symbols of devotion and cultural preservation.

Economic Life of The Barmans Tribe of Assam

Occupation

Agriculture is the mainstay, with rice, mustard, cotton, sugarcane, sweet potatoes, and vegetables cultivated. Ahu and Sali paddy crops dominate, supplemented by irrigation-dependent fields. Some families also engage in government jobs, teaching, policing, weaving, sericulture, animal husbandry, and cottage industries.

Weaving and Cottage Industry

Weaving is a prominent cottage industry, with women skilled in producing textiles for domestic use. Sericulture, rearing Endi silk worms, and brewing rice beer and molasses liquor supplement incomes.

Labor and Debt

Barmans generally avoid wage labor outside their community but work as forest contractors in Mizoram and Manipur. Advance payments often result in indebtedness, sometimes leading to land alienation over repeated cycles of forest work.

Hedari System

The traditional cooperative system, Hedari, allows community members to help families in need with cultivation, transplanting, harvesting, and storage. In return, families provide food and drink to volunteers, fostering mutual support and social cohesion.

Cultural Life of The Barmans Tribe of Assam

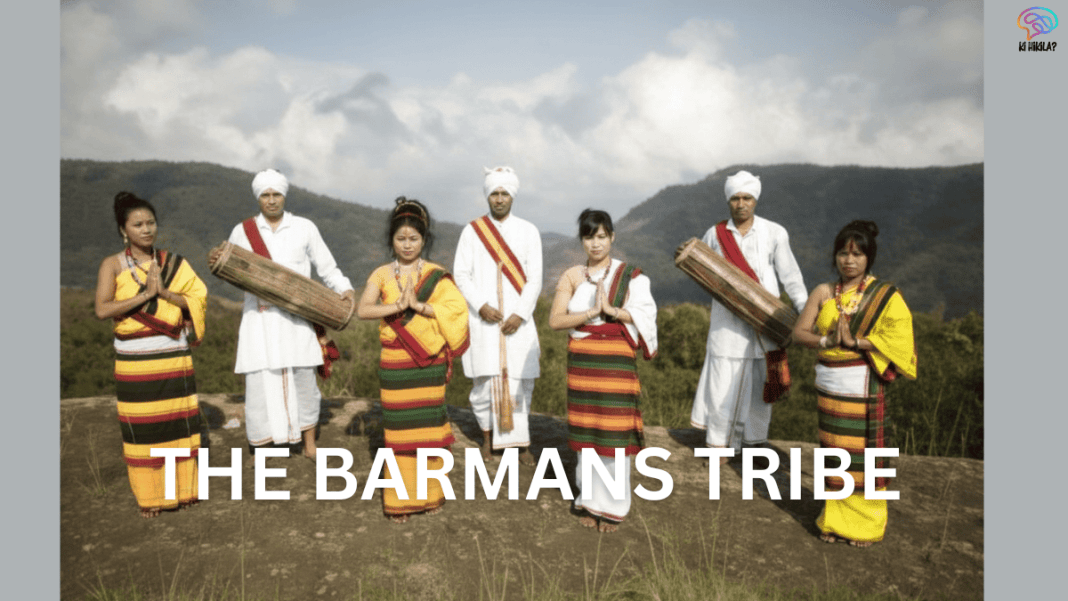

The cultural life of the Barmans is a vibrant blend of tradition, adaptation, and continuity. It reflects both their Dimasa heritage and the long-standing influences of neighboring communities, particularly the Bengalis and Manipuris. Despite these external impacts, the Barmans have successfully preserved their distinct identity through their archaeological heritage, music, dance, attire, food habits, and social practices, which together showcase the richness of their way of life.

Archaeological Heritage

The Barmans take immense pride in their ancestral legacy, which is vividly reflected in the archaeological remains scattered across Assam and neighboring regions. Sites such as Dimapur, Maibang, Khaspur, and Kasamari Pathar are living testaments to their glorious past. These locations boast remnants of royal palaces, majestic gateways, ancient temples, tanks, and other architectural wonders that speak volumes about the tribe’s artistic and cultural sophistication. At Khaspur, for instance, the Singhadwar (lion gate), the royal baths, and palace structures highlight the grandeur of the Barman rulers who once made this region their capital. Such monuments not only symbolize political power but also represent the community’s deep association with architecture, sculpture, and sacred art. For the Barmans, these sites are more than ruins—they are sacred reminders of their ancestry and cultural pride.

Dance, Music, and Attire

In earlier times, the Barmans shared the Dimasa tradition of folk music and dance, accompanied by indigenous instruments like Khram (drum), Muriwaitha (flute), and Suphin (string instrument). Over the years, however, the influence of Manipuri culture became prominent, largely due to royal alliances and social interaction. Today, traditional Dimasa music is rarely performed in its original form, having been replaced or blended with Manipuri-style devotional songs, Rasaleela performances, and festivals such as Holi. Still, music and dance continue to be integral to community celebrations, particularly during marriages and village gatherings.

Attire remains a crucial symbol of identity. Barman men generally wear dhotis, shirts, and occasionally turbans, especially on ceremonial occasions. Women traditionally wear a Mekhela-like garment called Rigu, often paired with the Rijamphai, a beautifully designed scarf. These outfits are usually handwoven, reflecting the skill of Barman women in weaving. Ornamentation also plays an important role, with traditional jewelry like Poal (necklace), Khamontai (earrings), Chandrawal (necklace), and Khadu (bracelets) enhancing the beauty of their attire. Although modern clothing has influenced younger generations, traditional dresses continue to be worn proudly during festivals and cultural programs, symbolizing respect for heritage.

Food and Drink

The dietary habits of the Barmans also reflect their agrarian lifestyle and cultural preferences. Rice forms the staple food and is consumed in various forms, complemented by fish, green leafy vegetables, pulses, and seasonal fruits grown in their kitchen gardens. On special occasions, meat dishes such as mutton and poultry are prepared, though pork is avoided as pigs are not reared in their households. Dry fish, often considered a delicacy, is also widely consumed.

Tea holds a special place in daily life, typically consumed twice a day, morning and evening. In addition, rice beer and molasses-based liquor, once deeply embedded in their traditions, had seen a decline due to religious influences but are now gradually witnessing a revival, particularly during festivals and community gatherings. These beverages not only serve social purposes but also represent the continuity of ancestral practices.

Conclusion

The Barmans of Cachar stand as a remarkable example of a community that has skillfully balanced adaptation with preservation. Over time, they have embraced the lifestyle of the plains, drawing influences from neighboring Bengali and Manipuri cultures, yet they have never lost sight of their ancestral Dimasa roots. Their acceptance of Hinduism, especially devotion to Siva or Sibsrai, reflects continuity of faith while still retaining a distinct cultural character. The cooperative spirit of their villages, evident in systems like the Hedari, highlights their emphasis on unity, mutual support, and social harmony. At the same time, their commitment to education has propelled the community forward, ensuring that younger generations are not only rooted in tradition but also equipped to thrive in modern society. Festivals, weaving, music, and oral traditions serve as living testaments to their cultural pride. Clean, well-planned villages and active cultural associations further illustrate their determination to safeguard heritage. Despite pressures of assimilation and modernity, the Barmans remain proud of their identity and continue to nurture a vision for a brighter, self-reliant future. Their story is one of resilience, adaptability, and cultural continuity, ensuring that the Barman legacy endures for generations to come.