The Tiwas Tribe of Assam, often referred to as the Lalungs, represents a vibrant and resilient indigenous community deeply rooted in the cultural tapestry of Northeast India. This ancient tribe, belonging to the larger Bodo ethnic group, has preserved a unique blend of traditions, myths, and social practices that reflect their migratory history and adaptation to diverse landscapes. From their origins in the Tibetan region to their settlements in the plains and hills of Assam, the Tiwas embody a story of survival, cultural evolution, and harmonious coexistence with nature. In this detailed blog, we delve into their etymology, migration, social institutions, festivals, and the evolving trends shaping their future, drawing from historical accounts, legends, and contemporary observations.

Introductory Overview: Who Are the Tiwas?

The Tiwas prefer to identify themselves as “Tiwa,” a name derived from their language where “Ti” means water and “Wa” means superior. This self-designation highlights their historical connection to rivers, particularly the Brahmaputra, which guided their migration to the plains of Assam. Conversely, the term “Lalung” was bestowed by non-Tiwas, with various mythical and historical explanations. According to the Karbis, “La” means water and “Lung” means rescued, suggesting the Tiwas found refuge along the Brahmaputra’s banks. Legends abound: one ties it to Lord Shiva’s creation from a stream of juice (“Lung”) and the formation of life (“La”), linking the tribe to divine origins. Another myth involves three daughters born from Lord Lungla and Goddess Jayanti, with the youngest giving rise to the Lalungs, alongside the Karbis and Boro Kacharis.

Mythical narratives further enrich the name’s origin. A popular story recounts how Lord Mahadeo, intoxicated with rice beer, created humans from his saliva (“Lal”), birthing the Lalungs. A variant describes five humans formed from saliva drops at Manasarovar Lake, earning them the name due to their divine creation. These tales underscore the tribe’s spiritual worldview, centered on animism and Hindu influences, particularly Shaivism.

The alternative name “Tiwa” may stem from “Tibbatia,” indicating Tibetan roots. Ancient divisions among Bodo groups—Tipra (Tripura), Tiwa, and Dimasa—lived near a Tibetan lake before migrating through northeast passes. Linguistic affinities, such as “Ti” or “Di” for water and “Mai” for rice, connect them to Kacharis and Tipperas, reinforcing their Bodo heritage.

Migration and Historical Settlement of The Tiwas Tribe of Assam

The Tiwas’ migration to Assam’s plains remains mysterious but is estimated around the mid-17th century. Historical records, like those from Ahom chronicles, note their involvement in regional conflicts, such as the 1658 rebellion where the Gobha chief sought Ahom protection, leading to settlements in Khagarijan (modern Nagaon). Socio-religious pressures, including aversion to Jayantia’s matriarchal systems and human sacrifices, prompted their descent from the hills.

Scholars like Grierson suggest origins in Jaintia Hills, with some claiming autochthonous status there. Lyall places them alongside Mikirs (Karbis) and Kacharis. As part of the Bodo race, including tribes like Rabha, Mech, Garo, and Chutiya, the Tiwas exhibit Mongoloid features: medium stature, strong build, fair complexion, flat noses, and straight hair.

Today, Tiwas concentrate in Nagaon’s Kapili, Mayang, Bhurbandha, Kathiatali, and Kampur blocks, with pockets in Meghalaya’s Jaintia Hills, Lakhimpur, Jorhat, and Kamrup. Hill villages in Karbi Anglong contrast with plains ones, influencing diets, attire, and agriculture. The 1971 census recorded 95,609 Tiwas, with estimates reaching 162,760 by 1987. Literacy stood at 21.5% (31.5% male, 11.26% female), below Assam’s tribal average but improving.

Daily Life: Food, Agriculture, and Economy of The Tiwas Tribe of Assam

Rice dominates Tiwa cuisine, supplemented by vegetables, meat, fish, and eggs. Pork and fowl are delicacies, essential for ceremonies, while rice beer (“Zu”) was once ubiquitous but is declining among plains Tiwas due to economic and educational shifts. Hill Tiwas favor “Kharisa” (bamboo shoot mixture) and dried fish, with “Zu” remaining central. Converts avoid pork and alcohol, opting for tea.

Agriculture, introduced by Austric ancestors, shifted from jhum (slash-and-burn) in hills to settled plough cultivation in plains. “Sali” paddy (from “Ha-li,” meaning wide land) is primary, with rituals like “Dhanar Muthi Lowa” marking seasons. Community harvesting (“Hauri”) involves rhythmic songs (“Mai Rawa”) and feasts, fostering social bonds.

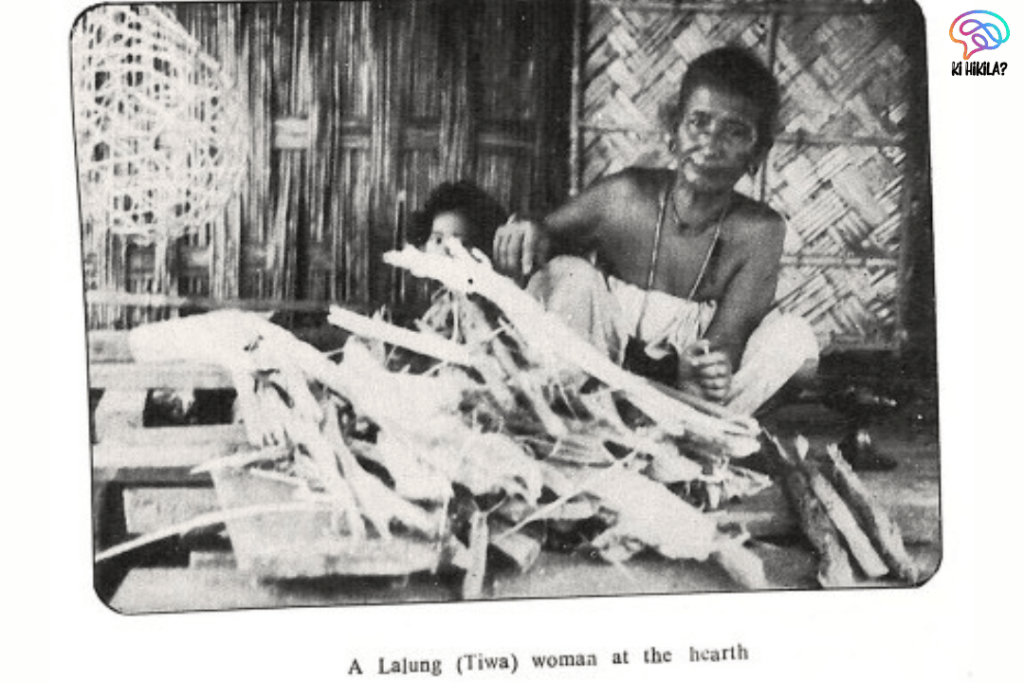

Hunting has waned, but fishing thrives, especially during “Jon Bila Mela” with group techniques using barriers and tools like “Pala” and “Juluki”. Weaving, bamboo crafts, and blacksmithing (evidenced by historical cannon-making in Kamarkuchi) support livelihoods.

Housing and Material Culture of The Tiwas Tribe of Assam

Plains Tiwa houses resemble Boro Kachari styles: raised plinths, thatch roofs, bamboo walls. The “Barghar” (cooking house) is sacred, housing deities; “Choraghar” entertains guests; “Majghar” is for sleeping. Granaries store paddy, with taboos like avoiding entry in Magh. Community halls (“Samadi”) train youths in arts, now fading in plains but preserved in hills.

Dresses blend tradition and modernity. Plains women wear “Mekhela,” “Chadar,” and “Riha,” weaving intricate designs. Men favor dhotis or trousers. Hill attire includes “Lengti” for men and breast-covering “Mekhela” for women. Ornaments are minimal: silver necklaces, bracelets like “Gamkharu.”

Arts shine in textiles, bamboo products (baskets, suitcases), masks for festivals, and musical instruments like “Khram” drums, flutes, and “Tandrang” violins.

Social Structure: Family, Clans, and Institutions

Tiwa families are nuclear, with patrilineal inheritance in plains (sons divide property) and matrilineal in hills (daughters inherit). Clans (“Wali” or “Kul”), originally 12 but subdivided, enforce exogamy: Macharang, Madur, Maloi, etc. Totemic clans worship specific deities, with hierarchies like “Bara Bhuni” but minimal social imbalance.

Titles (Deo Raja, Senapati) denote past hierarchy. Villages operate under “Buni” units with officials like “Gaonbura,” “Lorok,” and priests (“Gharbura,” “Zela”). Dormitories (“Samadi”) educate youths; Panchayati Raj governs politically.

Kinship uses descriptive terms, extending to outsiders. Marriage forms include elaborate “Bor Biya” (arranged with feasts), “Gobhia Rakha” (son-in-law resides), “Joron Biya” (simplified), and “Poluai Ana” (elopement, socially accepted). Bride price is nominal (Rs. 7-9). Monogamy prevails; divorce is rare.

Religious Beliefs and Festivals of The Tiwas Tribe of Assam

Tiwas follow Shaivism with animistic elements, worshipping Lord Mahadeo supreme. Deities include benevolent males (Ganesh, Parameswar) and females (Lakhimi, Kalika), propitiated at “Barghar,” “Than,” or “Namghar” for converts. Vaisnavism influences plains Tiwas, reducing animal sacrifices.

Festivals integrate worship, music, and dance: “Bisu” (Bihu-like), “Barat” (with masks), “Sagra Misawa” (harvest), “Wansua” (spring), “Jon Bila Mela” (fishing fair). Songs like “Lo Ho La Hai” accompany rituals.

Death rites involve cremation (common now) or burial, with purification ceremonies and “Karam” feasts for ancestors.

Changing Trends and Future Prospects of The Tiwas Tribe of Assam

Hill Tiwas retain traditions, including language and matriliny, while plains counterparts assimilate Assamese influences, losing language but gaining education. Economic challenges persist, but youth awareness curbs excessive festivals, promoting heritage preservation amid political awakening.

In conclusion, the Tiwas Tribe of Assam stands as a testament to cultural resilience, blending ancient myths with modern adaptations. With over 1,500 words in this exploration, we celebrate their enduring spirit, urging greater recognition and support for this invaluable indigenous legacy.